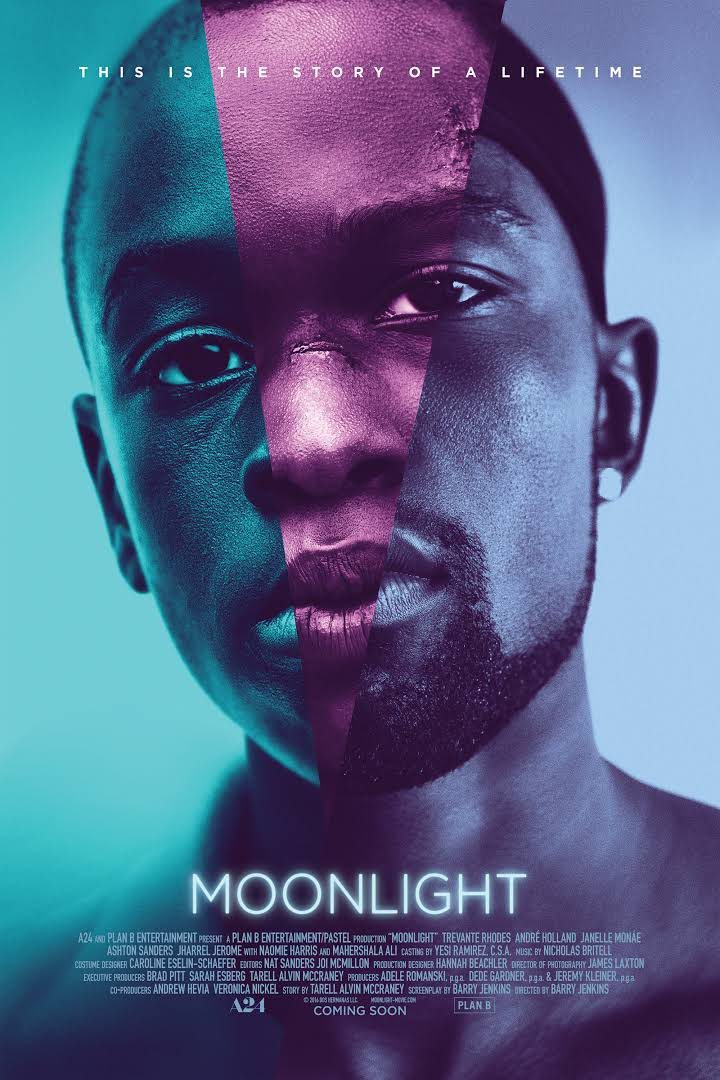

Casting a spotlight on Moonlight

The 2017 Oscar race is, unfortunately, with incredible historical precedent.

The arguable frontrunner for Best Picture, La La Land, takes the concept of jazz, a black-originated and still predominately black form of art and both whitewashes and romanticizes it.

It’s fitting that Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight, a bildungsroman with an entirely black cast, will likely lose to La La Land — it’s like Elvis Presley outselling Chuck Berry.

By adapting the historically strained methods of the black community, our predominantly white culture sells cultural caricatures to itself, ignoring and compromising the values inherent to those products.

It’s up to the individual to realize that Moonlight is the most important film of the past year.

It may not be the best film of the year — it may not even be as good as the compulsively watchable, gorgeous La La Land — but Moonlight straddles the line between art and reality.

The film’s protagonist, Chiron, is portrayed by three actors at three distinctly different ages. Their performances work to administer exceptional, yet unusual cohesion: Alex Hibbert, Ashton Sanders and Trevante Rhodes give superlative performances as the child, teen and adult iterations of Chiron, respectively.

But the film’s quality is especially cemented by the performance of Mahershala Ali, who plays a conflicted mentor to Chiron, all the while slinging crack on the street — including to Chiron’s degenerate mother.

It isn’t a predictably mapped film. In fact, in many ways, it’s startlingly mundane. But the visually immersive direction and the quiet, sparse, thoughtful dialogue between characters highlights the incredibly neutral perspective.

Moonlight is a film that inhabits its own space; when Chiron, a weak, bullied child follows his mentor’s path by selling drugs on the street, it isn’t shown as a last respite of despair. It’s a tiny victory, the slightest assertion of strength and absolute self-dominance.

In committing himself to a life of crime, he is finally granted a rewarding shred of power and dignity.

Virtually nothing in the film is sensationalized — the romance that blooms between Chiron and his childhood friend Kevin, is understated, sweet and sparked by a particular onscreen energy and chemistry between the actors. If anything, the stunted, uncomfortable dialogue works so well because it underscores the lucid nature of body language.

What makes the picture the objective best of the year? Is it effects, dialogue, direction or maybe the visuals? It’s nearly impossible to state a singular, objective purpose to the multivalent medium of film. But by a modern, cultural context, Moonlight is the film that the world needs.

Anything that can bridge a gap, making something as distant and specific as a gay black kid steeped in the gang culture of Miami into something universally real and relatable to even white, heterosexual Canadian audiences, and without the slightest sign of pandering, is hard to overstate the importance of.

In a superficial way, the bits and pieces of Moonlight feel like a direct response to the #OscarsSoWhite boycotts of 2016. But the reality is much more amazing than that.Moonlight is an expression — a small film with big ambitions and a very real soul. Through non-conformity, Moonlight transcends.

However, how the Oscars play out doesn’t really matter. History and perspective adjust to reality. Forrest Gump beat out the far superior The Shawshank Redemption in 1994 and The King’s Speech overtook the flawless The Social Network in 2010.

Ten years from now, here’s hoping (and believing) that the world will still be talking about Moonlight.