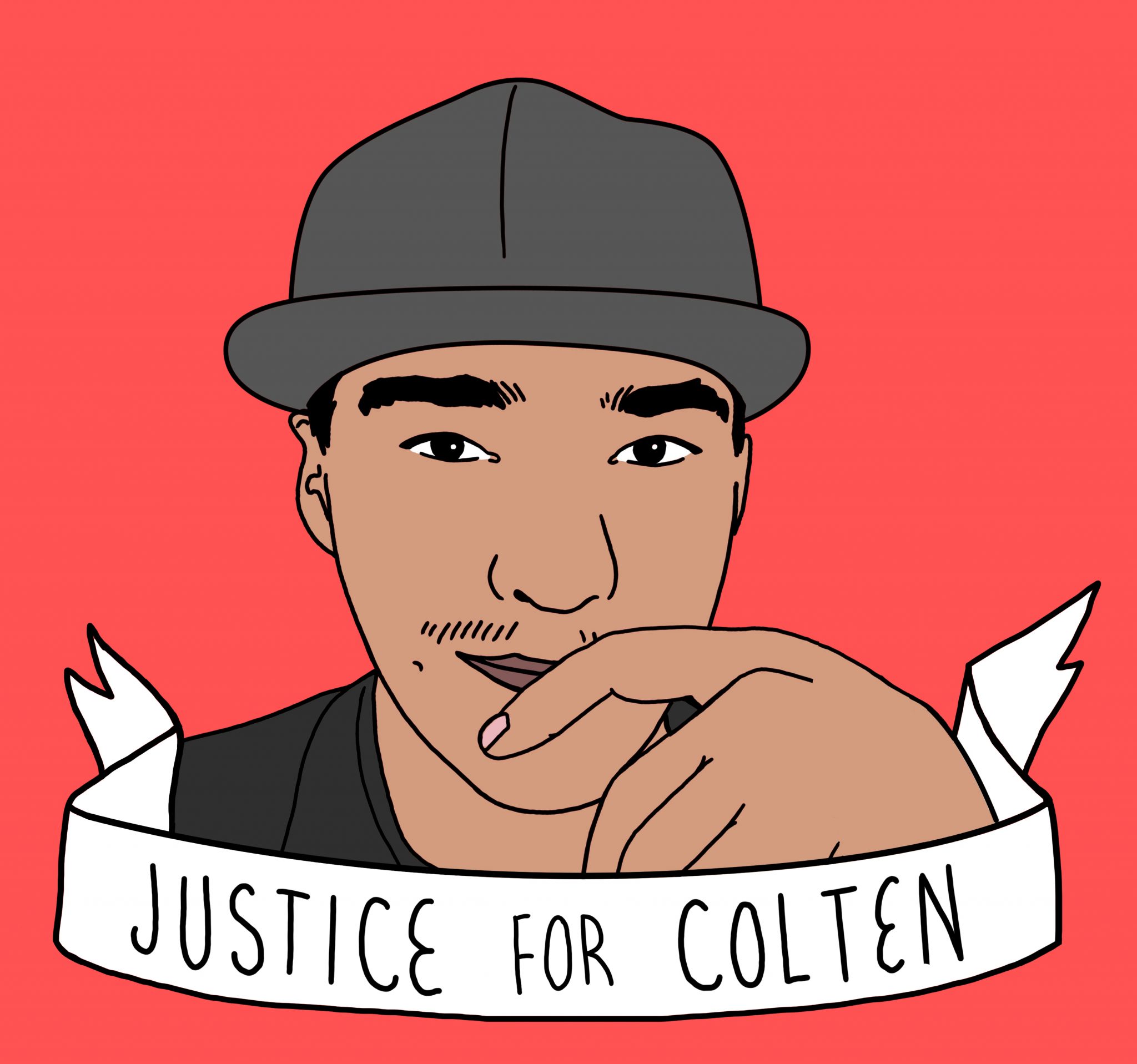

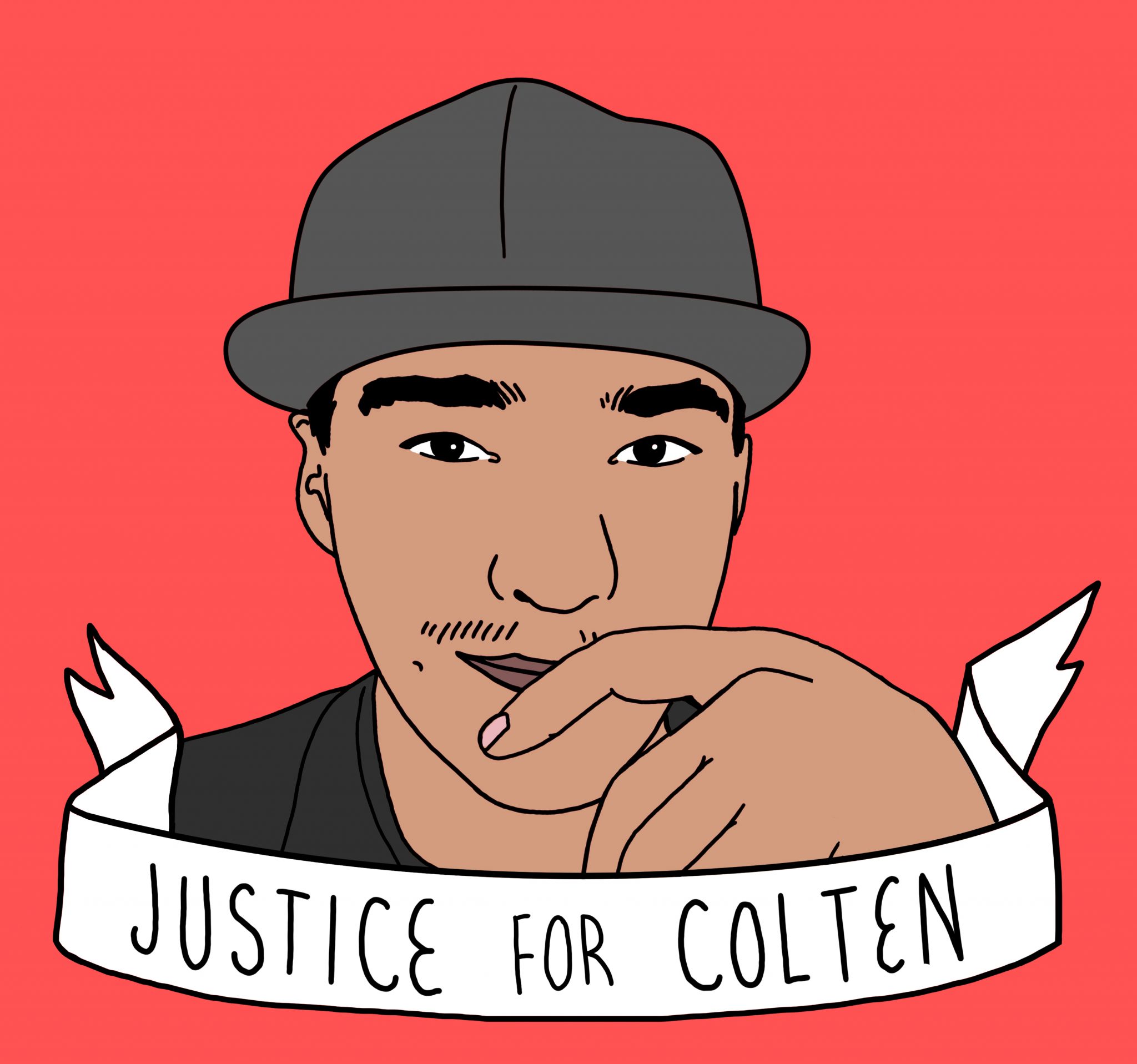

Waterloo hosts Justice for Colten event to acknowledge murder of Indigenous youth

On Aug. 9, 2016, 22-year-old Colten Boushie was fatally shot by Gerald Stanley. Boushie and five of his friends drove from the Red Pheasant Cree Nation onto Stanley’s farmland property which is located near Biggar, Saskatchewan.

After an altercation with Stanley and his family, Boushie was shot in the head, after which 56-year-old Stanley was charged with second-degree murder.

In defence, Stanley’s attorney claimed the gun fired by Stanley was “accidentally on delay,” further known as “hang fire.”

However, on Friday Feb. 9, 2017, Stanley was found not-guilty by the Battleford Court of Queen’s Bench jury, instilling emotions of fear, disappointment and grief amongst Boushie’s family and Indigenous communities all over the country.

In correspondence to the acquittal of Stanley, rallies and gatherings have been taking place in communities all over Canada in Boushie’s honour.

In the Waterloo Region, community members organized a gathering at Victoria Park in Kitchener on Feb. 11.

“The intent of [the] gathering was to provide a space of reflection and coming together in a time where a young Indigenous person was unlawfully murdered, yet again,” Jacqueline Pelland, community organizer of the gathering, said.

Approximately 40 people showed up to the gathering, which ultimately aimed to provide a space for Indigenous people and community members to show their support.

Those in attendance shared songs and listened to individuals speak on behalf of the dynamics that were involved with Stanley’s trial from the beginning up until the final acquittal.

“Colten’s case is not anything new. For as long as I can remember I pretty much hear yearly about how Indigenous youth are either murdered by police or white community members, abducted, dumped in rivers, that sort of thing,” Pelland said.

As a result of yet another instance of a racialized youth being murdered without alleged justice, Pelland explained that many may feel discouraged to continue attending events and gatherings that, ultimately, don’t seem to end these occurrences.

“There’s essentially no actual justice being brought forward in terms of the perpetrators of those crimes.”

Pelland explained that, for many Indigenous people, Boushie’s case has been a boiling point stemming from so many similar prior court rulings.

“This gathering was sort of an acknowledgement of everything that’s come before the trial’s decision in terms of the quote-un-quote progress that the government has advertised and supported and that the justice system has explained to be sufficient is clearly not [enough],” Pelland said.

“There’s definitely a lot of feelings surrounding that as an Indigenous person, and communities all over the country are really feeling the fear from that,” Pelland said.

As a result of yet another instance of a racialized youth being murdered without alleged justice, Pelland explained that many may feel discouraged to continue attending events and gatherings that, ultimately, don’t seem to end these occurrences.

However, Pelland believes that gatherings and rallies still hold meaning and value.

“I do believe that there are people who want to do better. So they attend these events in an attempt to do that and to hold themselves accountable and learn how to hold the people in their lives more accountable,” Pelland said.

More importantly, the words of Lori Campbell, director of the University of Waterloo Aboriginal Education Centre, who spoke at the event, summed up the importance of speaking out in a time when so many voices are being silenced.

“[Campbell] said that the one thing that people can’t be right now is silent. And that’s something that’s really tied into the abuse that Indigenous people have suffered; the idea that everything will get better if you stay silent,” Pelland said.

“That was told by the priests and nuns that abused Indigenous children in residential schools; just stay quiet, don’t tell anyone and you’ll survive. It was told to my Métis ancestors who were told ‘don’t tell anyone that you’re Indigenous, tell people you’re white and you’ll survive.’”

In addition, at the gathering Campbell spoke to the true structure and the way in which Boushie’s case was presented within the court system. Importantly, Campbell noted the individuals by whom the information was presented.

“There are people involved in the acquittal of Gerald Stanley who previously were defending a known white-supremacist,” Pelland said.

With Boushie’s case, the judge was Caucasian. Similarly, the jury was made up of few to no Indigenous individuals.

“All of these legal systems are stemming from a colonial basis so regardless of what sort of narrative people are working with, those are facts, those are things that exist now, even beyond Colten’s case, and they’ll likely continue to exist,” Pelland said.

“And that’s not something people can ignore.”