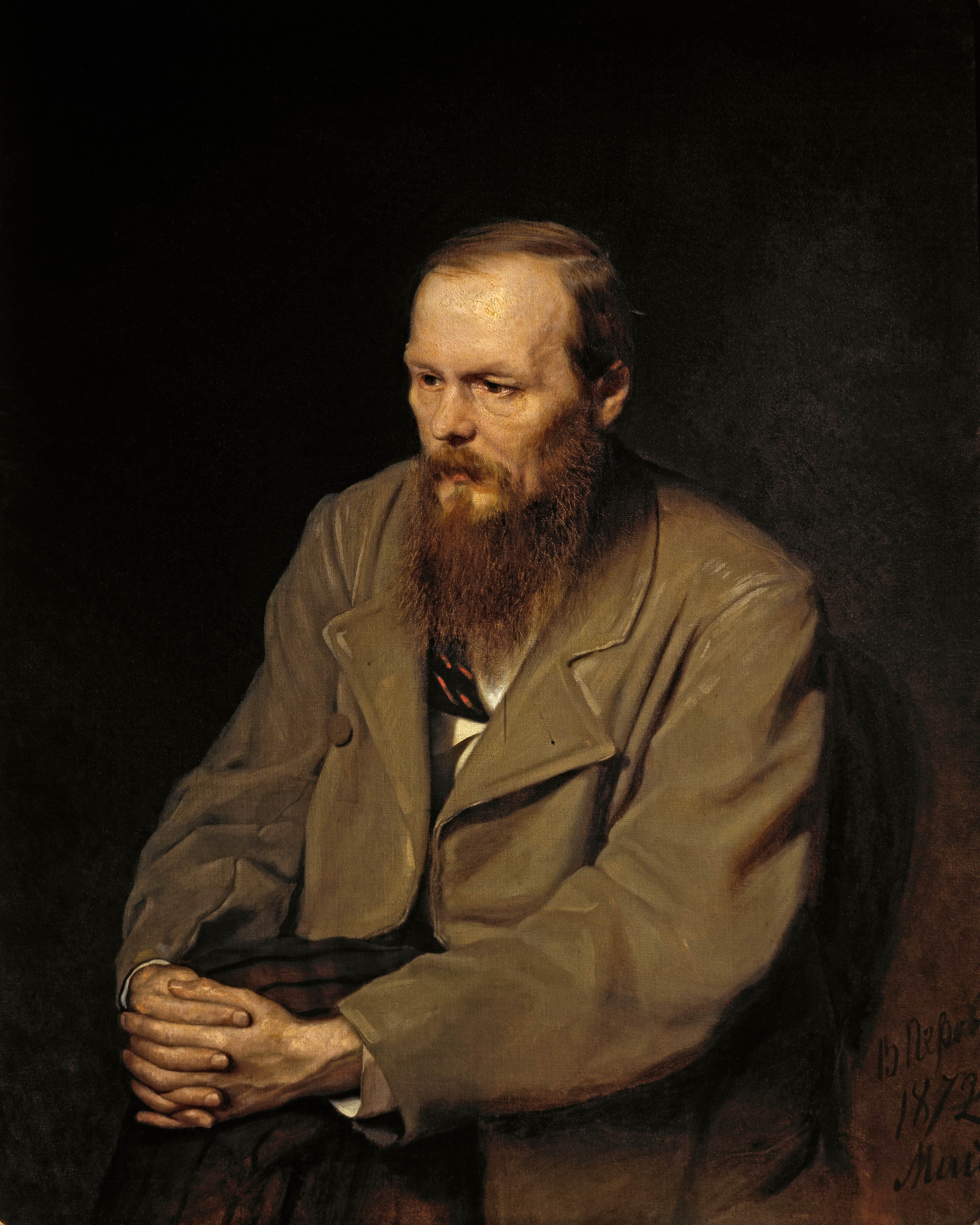

Recounting the wisdom of Dostoevsky

Unraveling the philosophies of an iconic Russian novelist and how his words can help our lives

There are some psychologists who refer to the great Russian novelist, Fyodor Dostoevsky, as a “psychologist among psychologists.” Among them, Sigmund Freud agreed and wrote an insightful essay on “Dostoevsky and Patricide.”

Dostoevsky is considered one of the precursors of psychoanalysis and existentialism.

To me however, he was first and foremost, simply and hugely: Fyodor Dostoevsky.In what many critics agree is his finest and most layered novel “The Brothers Karamazov,” Dostoevsky identified three essential human needs, often those determining much of human behavior.

He began with “bread,” symbolizing the sum total of all material goods necessary for survival. Dostoevsky wrote with a touch of irony: “There is no crime and hence no sin, but only those who are hungry.

Feed them first and then demand virtue of them.”

But the novelist denied that material comfort was the sole criterion of our contentedness.

He also wrote: “Human beings must also be understood because the mystery of human life is not only in how to live but what to live for.

Even knowledge of the meaning of life cannot satisfy our hunger for transcendence, if we are the sole bearers of that knowledge.” We need to share our ideas with other members of the human family.

The third and final need is for what Dostoevsky defined as “universal synthesis.” We struggle to make everything universal.

According to the Grand Inquisitor (The Brothers Karamazov), people are more eager to accept “miracles, mystery and authority” than remain in agonizing uncertainty.

We need to centre ourselves in our world. Freedom of choice is too burdensome and brings loneliness and a sense of isolation; we need to belong to someone, belong somewhere and center ourselves in our sacred place in the cosmos.

To live, to know and to belong — these define the basis of human behavior. Dostoevsky wrote: “Human nature is not only something dark and cruel, but also something bright and exalted.

Goodness, pity and conscience are as deep and resistant to external influences as are cruelty and egoism.”

And here the great novelist speaks to the dialectical duality of human nature.

Accepting our social inheritance contains not only the great victories of the human spirit but also the weight of darkness, selfishness and evil that follows us on our brief walks across eternity.

The good however was Dostoevsky’s greatest hope.

For him, the critical factor of opposing the selfish tendencies of the individual was empathy — that ability to perceive and feel another’s pain as one’s own.

For Dostoevsky, compassion was the saving path to God, but he argued too that we could analyze compassion outside the religious and mystical context of his collected work.

Not only can we understand brother Alyosha’s religious orientation but we can grasp fully too, brother Mitya’s more secular approach to the same important issue.

In his novel, “Crime and Punishment,” Dostoevky’s anti-hero Raskolnikov — the axe murderer — was not tortured by anxiety, weakness or even helplessness when trapped by wily detective Porfiry Petrovich, investigating the double homicide. Rather, he was tormented by that which he could not suppress — his own humanity, that which connected him to all others, a humanity which Sonya, his friend and salvation, most clearly saw.

Raskolnikov said: “If only I were alone and nobody had loved me and I had never loved anybody. Things wouldn’t have been that bad.”

Through all of Dostoevsky’s novels, all faith rests on the fundamental belief in the deep and enduring humanity in each of us, even in Raskolnikov.

Compassion allows you and me to feel, almost physically, those dehumanizing influences exerted on another person.

Dostoevsky knew that people who have not internalized the world of another person would find it difficult to experience themselves as fully human beings.

He wrote: “The labor (sic) of the soul is to suffer, to feel the pain and suffering of all humankind … and first of all, one’s mother, father, sisters, brothers and grandparents. Do not be afraid to open a young soul to these sufferings — they are full of dignity.

Let a 13-year old so spend the whole night at the bedside of his ailing mother or father … let their pain fill all the deepest recesses of his young heart.

One of the most painfully difficult things in education is to teach the child the labor of love.”

In a world where many of us suffer from alienation, of one form or another, it is good to remember that central wisdom revealed in Dostoevsky’s novels.