Floating to reprogram the mind

The quarter-life crisis hit hard. Questions flurried in my head. Is this the right path? Am I chasing the right thing? Will I find fulfillment in the end? Fermenting in frustration could only get me so far.

Psychedelic experiences present the potential for brain plasticity, which is certainly a desirable state for many, but the unpredictable nature of illicit substances can lead someone astray. But you don’t need drugs to reach that frame of mind. One can embark in the “metaprogramming” of the “human computer,” as described by neuroscientist John C. Lilly, through sensory deprivation therapy.

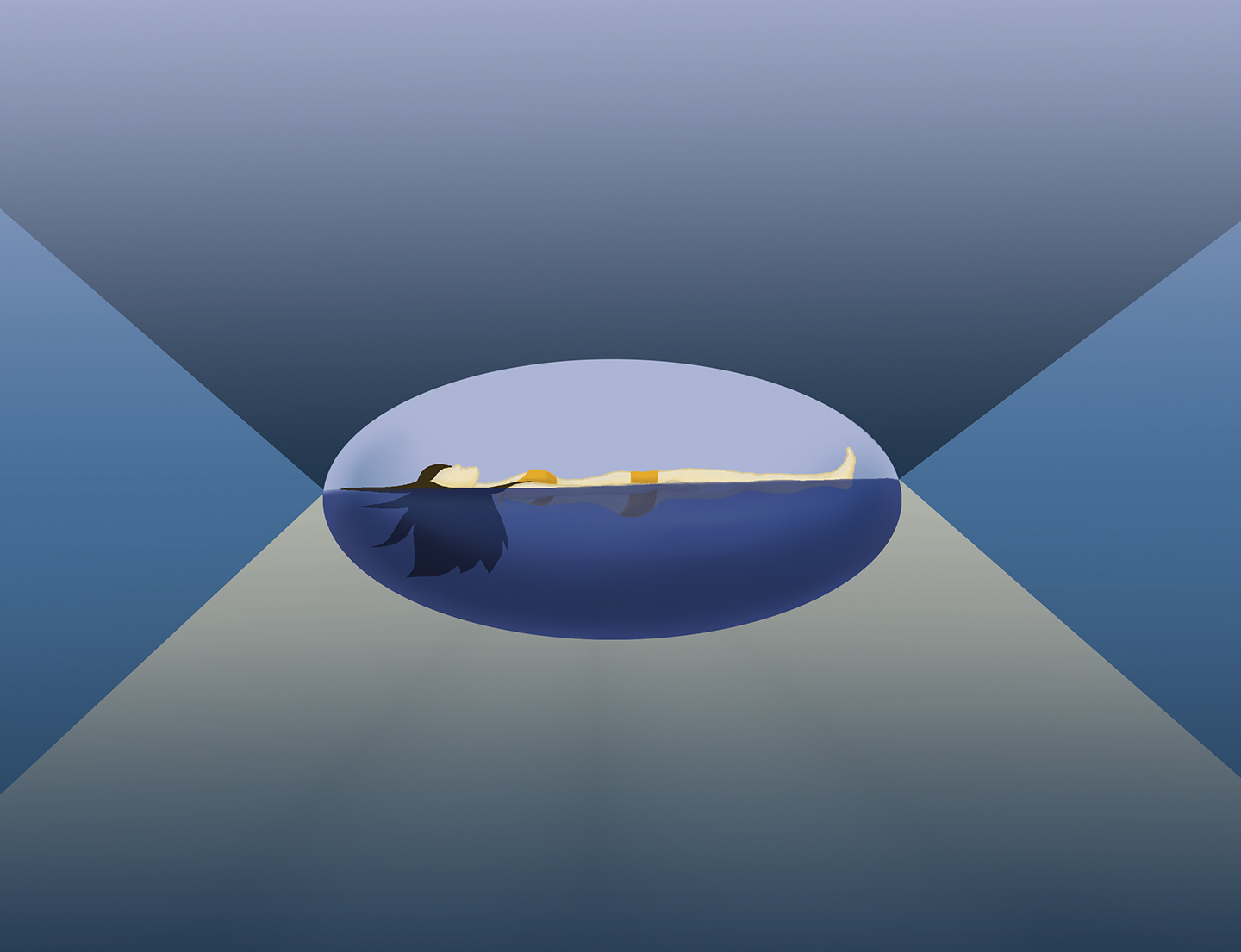

Lilly is considered the founding father of sensory deprivation therapy through use of isolation tanks, or more gently known as “float” tanks. These tanks isolate users in complete darkness within a neutral space free of discrete smell or sound. Suspended in only inches of extremely salient and buoyant water at a temperature consistent with the subject’s skin temperature, the environment is meant to subdue any feeling of touch or motion. At the absence of sensory stimulation, it’s much simpler to focus and possibly manipulate the thinking process.

Flowt K-W, a young establishment north of the Wilfrid Laurier University Waterloo campus, specializes in sensory deprivation therapy. The establishment has garnered the curiosity and commitment of many community members bent on addressing physical or mental concerns by floating for up to 90 minutes.

“Your brain and your mind follow your body,” said Arend Okkema, co-founder of Flowt K-W.

“Psychedelics are like a slingshot out into the sky and it’s like you don’t know what might necessarily happen … [floating] is much more of a controlled state.”

Floating first caught the father-son duo’s attention upon hearing about Christian Zrymiak, a Saskatoon entrepreneur who put his own float tank in a school bus, giving multiple people the “float” experience as he journeyed to music festivals along the coast of British Columbia.

Both Mark and Arend Okkema, intrigued by the unique business, tried floating and found it incredible. Noticing the lack of float centres in the Kitchener-Waterloo area, the duo felt that community members ought to reap the therapeutic benefits and opened the business.

I floated and it was marvelous.

“You’re only going to hear two things: your breath and your heart,” said Mark Okkema, co-founder of Flowt K-W and Arend’s father.

After a brief conversation with the duo, it was time. Arend gave me the introduction, offering tips on how to float safely, comfortably and positively.

Earplugs, shower, float.

I began recalling the horrendous swimming lessons of my youth, where I struggled to float even when using the assuredly buoyant star formation. But the hyper-buoyancy of the float tank water mitigated any chlorine flashbacks. The warm salient water enraptured my naked body, enveloping me in a comforting, fluid cashmere. But if I wanted to program my brain, I thought, I couldn’t just float there.

The first five minutes were spent capturing any fleeting thoughts, to find something purposeful and focused. I imagined if I focused on my mental conflict long enough, the abstract function of the float experience would take course and I would emerge satisfied and fulfilled.

But this proved difficult, so I tried to make something of the colour aberrations burned into my retinas and eventually, sensations in my fingers began to fleet.

“There’s a sensation called nerve stagnation and that’s where your nerves actually stop sending signals back to your brain that they’re getting any input,” said Arend Okkema.

“Because you don’t have any sound to judge by and you don’t have any light to judge by, you really don’t know where you are in terms of everything else. That’s called your loss of proprioception.”

I then began to use visualization in a more abstracted manner. Rather than playing with tangibles, I pictured the ideal future, visualizing true fulfillment. My relaxed state intensified.

Some ambiguous time later, I emerged from a dark void, recollecting sensation in my extremities and realized I was still floating in 200 gallons of warm, salient water.

“Shit,” I thought. “I fell asleep, I missed it.”

In that very moment, I was convinced that my goal to achieve some abstracted serenity had been botched by selective narcolepsy. A subtle chime signaled the end of my float. I emerged from the tank and stumbled to turn on the light. Even at its dimmest, the illuminated room was straining.

As I walked to the front desk after getting dressed, Arend’s voice bellowed with apparent depth even at speaking volume.

“A lot of people experience a sensory reboot,” said Arend Okkema.

The duo assured that the dreamless, dark void was a delta brainwave state, a deep and regenerative experience.

Sitting in the vanity room, sipping peppermint tea, I reflected on the float. Although my experience didn’t recall that of a “disembodied mind floating through the universe,” it felt intangibly meaningful.

“Almost everyone will agree that they’ve experienced something that they have a very difficult time putting words to because it’s so different,” Mark Okkema explained.

I’m still here with questions abound, floating didn’t answer them, but it could help me get there in time.