Discussing water disputes, shortages in the Middle East

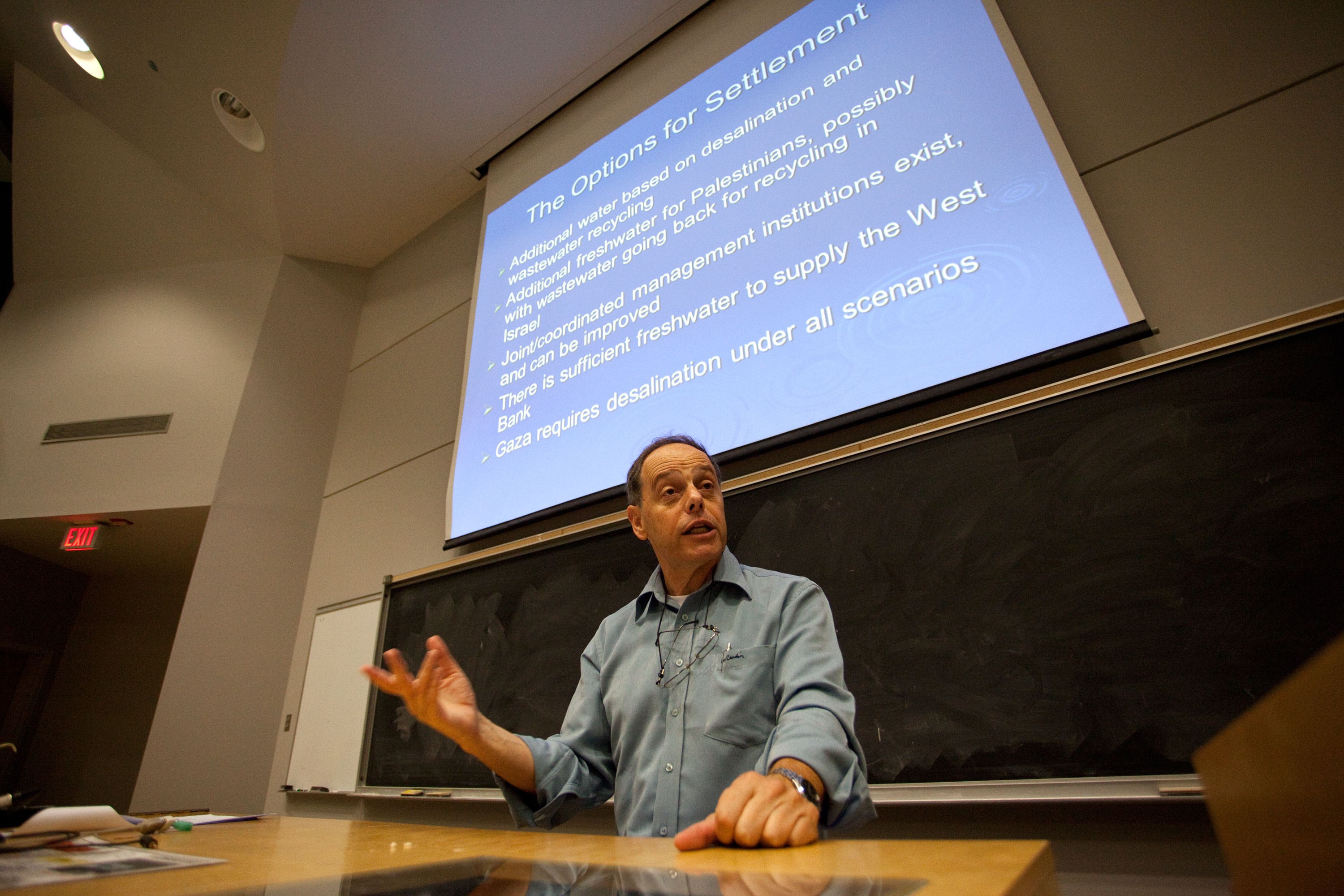

Last Friday, Eran Feitelson, a professor of geography from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, gave a lecture entitled “The Options and Impediments to the Israeli-Palestinian Water Dispute” at Wilfrid Laurier University.

The topics discussed ranged from the geography of water in the Middle East to the issues of water storage and joint-management between Israel and Palestine.

“Most of the projects that we talk about are joint Israeli-Palestinian projects,” said Feitelson.

“In terms of the basic dispute… most of Israel’s water is derived from shared resources, the mountain aquifer [and] the Jordan River.”

Israel’s National Water Carrier, completed in 1964, connected all surface water basins from the Sea of Galilee in the northeast to the metropolitan areas in the coastal plains.

“But the main water source of the region is the groundwater,” explained Feitelson.

The groundwater is mostly located in mountain aquifers within Palestine as the geography of the Jordan Rift Valley causes water to naturally flow from tributaries around the Eastern Lebanon Mountain Range into a series of springs underneath the Samarian and Judean Highlands.

Feitelson stated that in the case of the Middle East, with long periods of drought, “storage is the name of the game.”

Groundwater is particularly useful in this sense because it is not vulnerable to evaporation, and can be used to increase storage capacity.

Israel also uses industrial processes such as desalination and recycling of wastewater to increase the amount of the water supply that is “insensitive to climate and weather.”

However, given the location of storage resources Feitelson recognized that Israel and Palestine will need to manage the shared aquifers.

“The discussion usually begins as some zero-sum game, a view which essentially says where one side gets more, the other side gets less,” explained Feitelson.

“There is a limited resource and all the [political] entities — Israel, Palestine, Jordan — are in extreme water scarcity.”

Feitelson also pointed to the issues of rapid population growth in the region and the corresponding increase in per capita demand to follow in the economic future.

“However, the zero-sum game is actually outdated,” he claimed.

He proposed that the debate would be better handled if parties would “cease to talk about historical rights” and look at the issue in the economic realm to “de-politicize the issue.”

Israel’s industrial water system is used to transport desalinated seawater from the coast inland, but despite increasing overall water supply, so that the zero-sum game becomes more flexible, the level of distrust between the parties limits the possibility of cooperation.

“The Palestinian Water Authority recognizes that at some point in the future there will be a need for desalination but [doesn’t] want to be dependent on [it],” stated Feitelson.

Instead, according to Feitelson, it would exercise a higher degree of sovereignty over the pumping of the mountain aquifer resources, of which the per capita use amongst Israelis is disproportionately more than that amongst Palestinians.

“Desalination is part of the solution but is not the whole solution,” concluded Feitelson.

He finished by explaining that basic power relationships are intrinsically changed between both parties with Israel being upstream and in control of the water sources.

Ultimately he argued that the question of “who will control the storage” must be answered through joint water management.