Canada’s increased immigration targets: great for labour, not so good for housing

Last year, Canada broke its annual immigration record with 405,000 newcomers. The nation will continue to break this record until at least 2025.

According to a plan revealed by Sean Fraser, the Canadian minister of immigration, Canada aims to welcome 465,000 permanent residents in 2023, 485,000 in 2024 and 500,000 in 2025.

The catalyst for such target-setting was largely the labour shortage Canada finds itself in, which would likely worsen without continuing (and increasing) significant immigration levels.

Jason Dean, an assistant professor of economics at King’s University College at Western University, believes the cause for current shortages was, among other things, an aging population and pandemic-induced economic complications.

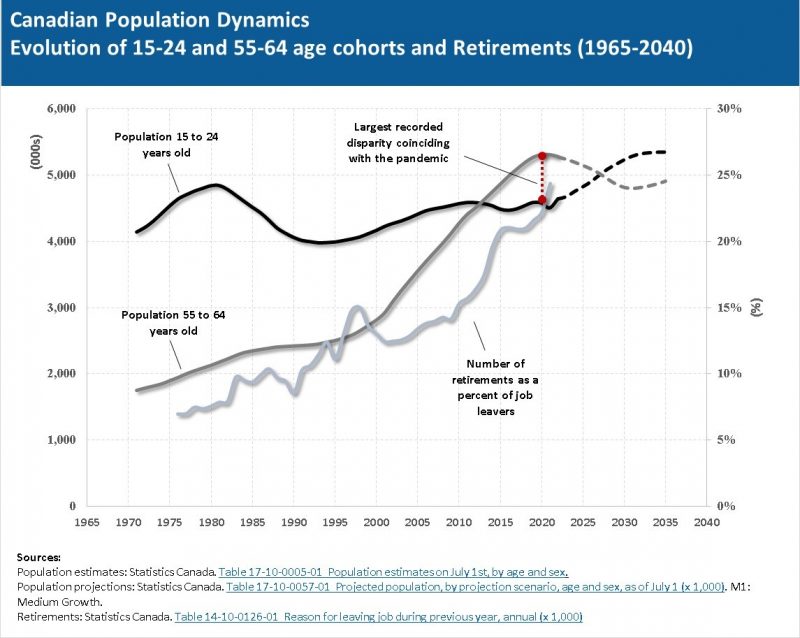

“The main culprit behind these shortages has been staring policy makers in the face for decades. Canada’s working-age population has never been older and there are simply not enough younger workers to replace a rising tide of retiring workers,” Dean wrote in a report shared with The Cord.

“The reason why we are facing a labour shortage is abundantly clear – the outset of the pandemic coincided with a historically high divergence between those old enough to retire and the number of younger labour market entrants,” the document reads.

“It’s just pure demographics … we need new younger people to enter the labour market,” Dean said. Immigration is one such way to make this happen.

Two consequences of this pattern are, among other things, a shrinking labour force and an elderly population lacking adequate support.

“Our baby boomers are retiring … number one, we don’t have enough people to pay the taxes to support pensions in the end and number two, we are not going to have enough labour to take care of them,” Stacey Wilson-Forsberg, author of two books on immigration and associate professor of human rights and human diversity at Wilfrid Laurier University, said.

Wilson-Forsberg warned that an aging population could mean Canada records more deaths than births in the future.

“Our deaths are going to start outnumbering our births pretty soon … so, from a demographic point of view, [immigration] is very, very important,” Wilson-Forsberg said.

“Immigration is really Canada’s only form of, not only population growth, but stabilizing the population, so we don’t start decreasing in numbers.”

While the numbers show that Canada needs significant levels of immigration to restore labour equilibrium, it is less clear how the country will juggle an already out-of-control housing and affordability crisis with 1.45 million new residents by 2025.

According to an article from the Wall Street Journal, Canada’s national housing agency the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. declared that 3.5 million additional homes must be built by 2030 in order to restore housing affordability.

“It takes a lot of time to build housing … I think the increase in immigration is definitely a positive long-term thing, but I cannot see how there wouldn’t be some substantial short-term issues with housing, because there’s already not enough homes,” Dean said.

Another concern is that demand for housing will increase as more newcomers arrive in Canada, thus increasing prices in a building market already teeming with inflation.

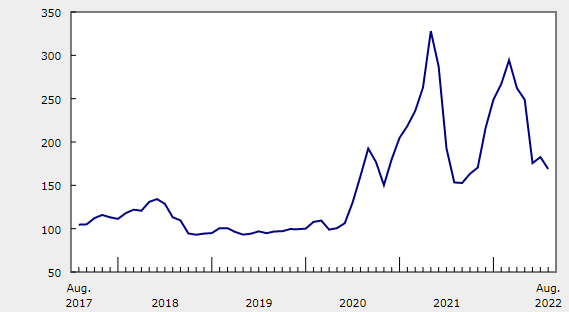

Building materials like lumber have dramatically increased since 2020 when pandemic policies sent shockwaves through virtually every corner of the Canadian economy.

These prices are still very high, according to Dean.

“I don’t even know if it’s feasible to build those homes if they’re going to just drive up the prices of those inputs even more,” Dean said.

“I really see the need for more immigration given the demographics and the labour shortages, but yeah I don’t see how we are going to meet their housing needs in the short-run.”

To help alleviate these affordability and housing strains, the government of Canada intends to place new immigrants in small towns and rural communities. This is meant to keep prices as low as possible and supply high in those regions most impacted by affordability and housing problems – i.e., city centres and immediate surrounding areas.

In smaller towns and rural areas, houses are much cheaper than in/near big cities. “That might be a very good incentive to encourage people to come to smaller places,” Wilson Forsberg said.

Wilson-Forsberg focused her PhD research on immigrants in smaller towns and rural areas. She said that this kind of move can come with challenges.

“People tend to stay in the small places for a while and then they tend to take a secondary migration to Toronto, or Edmonton or Vancouver because that’s where family members tend to be, their social networks are there, their ethnic networks are there. So, of course, it’s a challenge.”

“It’s rare when small towns get to actually keep people,” Wilson-Forsberg said.

Yet another factor comes into play when immigration is dispersed into smaller towns and rural areas: support systems.

“If Canada really wants to disperse people away from Toronto and into smaller places, they have to make sure that the services are there to be able to support people,” Wilson-Forsberg said.

If the support structures are not there, “outcomes might not be all that great, which is a whole other issue,” Dean said.

The Immigration Levels Plan released by Fraser also claims that the Canadian government will continue to provide “support for global crises by providing a safe haven to those facing persecution.”

While just over 60 per cent of new permanent residents will be in the economic class by 2025, it is not clear what percentage will be refugees. However, this term can be misleading.

People who are ‘refugees’ are not necessarily more burdensome to the Canadian economy; they do not always require more support than those in the economic class.

“If people are coming in the humanitarian class as refugees, [that] doesn’t mean they’re not skilled. That doesn’t mean they’re people we have to take care of and they’re victims … these could be highly educated professionals as well who have lost everything,” Wilson-Forsberg said.

“Even if they’re not, they still come in and they do very well for themselves, they work very hard. So, any category of immigrant – humanitarian, family class – are helpful to the Canadian economy and society in the end.”

Like most things, immigration clearly admits a virtual infinitude of nuance. Given the current state of Canada’s labour market and our aging population, immigration is not only good – it is necessary. This said, good things can bring immense challenges too. Whether Canada is ready to face such challenges without worsening the affordability and housing crises is yet unanswered.