Humanizing homelessness in the KW region

Last year, the region of Waterloo set an ambitious goal to end chronic homelessness by Jan. 2020.

That objective could not be met by their projected timeline, as the issues that people experiencing homelessness are facing are far more complex than what can be solved in a matter of months or a year.

As well, shelters are seeing longer stays coupled with an increase in the number of beds that are required, which complicates the region’s ability to adequately address the needs of each individual.

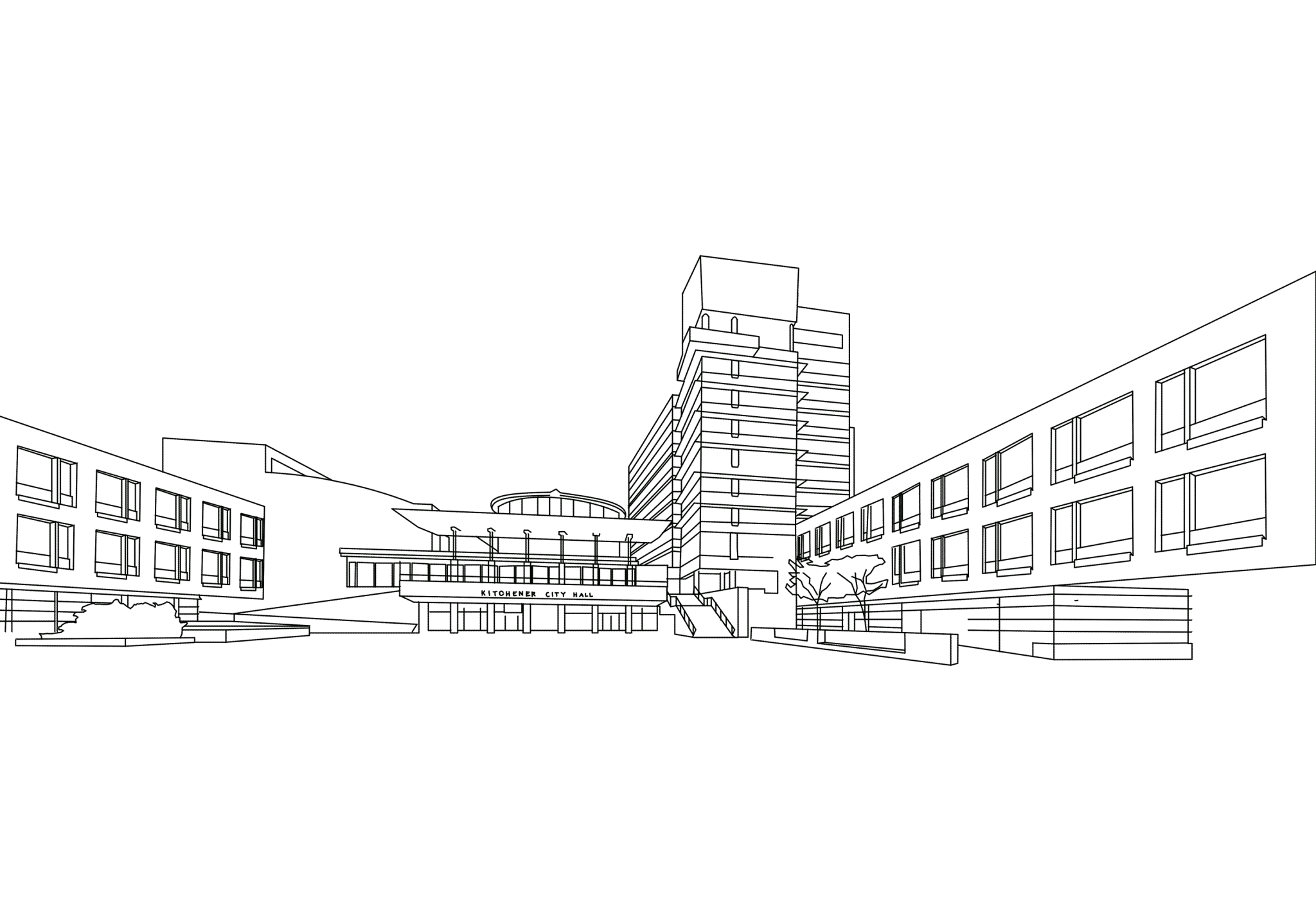

With the growth and development of Kitchener’s downtown core, the gentrification of the area has caused a noticeable social divide.

For a city that has built and established many notable support systems for those who are experiencing and impacted by urban poverty, the prioritization of building more high-priced condominiums in order to fit the growing demand to “revitalize” downtown Kitchener seems to be contributing to problems that are being overlooked, rather than working towards attainable, long term solutions.

For people experiencing homelessness in the Waterloo region and cities across Ontario, they are also faced with a multitude of various systematic challenges and setbacks.

Steve Abdool, RN, MA and Ph.D. staff bioethicist at St. Joseph’s Health Centre and St. Michael’s Hospital believes that the social perception of homelessness can be one of the most limiting factors in terms of putting valuable assistance in place for those who need it.

“I think the first thing they experience, these human beings — our brothers and sisters, parents and children, it’s not ‘us’ and ‘them’ — they experience a lot of stigma, labelling, discrimination — stigmatization is very, very high in our society,” Abdool said.

“Another thing, around stigma and labelling, is [the belief] that these people are a threat of violence and dangerousness in our society — that’s not the case at all. Hundreds of studies have shown they are not at [higher] risk than the rest of the population for dangerousness and violence to others in our society. So we need to dispel that [myth].”

For people who are also living on the streets with mental illnesses, the difficulties they face are prevalent and made more complicated as well.

“Oftentimes they can’t afford the[ir] medications, and because they have no fixed address, they [can’t] get an OHIP card — so we need to look into those systemic issues,” Abdool said.

“[As] a community, we’re so intolerant of these people who have serious and persistent mental illnesses, that we label them and discriminate against them.”

As someone who has lived in DTK for most of my life, these prejudices are starkly apparent and visible when walking through this area of the city.

People who are visibly experiencing homelessness are ignored, harassed and discriminated against as though they aren’t human beings.

The municipal and local perception often seems to centre on the notion that these people are unpleasant fixtures who should be ignored and pushed out in the process of refurbishing a city that would rather have a flourishing tech community, along with rising living costs, than care for a struggling community that’s continuing to expand.

No, they don’t have ready access to care, treatments, support, compassionate care and teaching them the skill sets to be more hopeful, rather than [feeling] helpless … There’s a lot of work to be done.

– Steve Abdool, Ph.D. staff bioethicist at St. Joseph’s Health Centre

“As our society becomes more and more ‘Trumpian’ in its orientation — very capitalist in its orientation — there’s going to be a bigger divide between the ‘have’ and the ‘have nots.’ When you look at the wealth in Canada … something like seven per cent of Canadians own [roughly] 90 per cent of the wealth in Canada. That makes you think ‘how about the rest?’ … that’s a big issue,” Abdool said.

“Studies have shown that more and more people are becoming homeless, and more and more family members — not just individuals … we know that more and more children are accompanying people to [food banks] … so now they have to modify what they’re giving out, especially during the winter months.”

Providing effective care and connections to those who need them are fundamental for people who are experiencing homelessness in order for them to be properly supported.

“Access to supports and resources. In this whole area here, not unlike Toronto, it takes eight months to see a psychiatrist, an addictionologist … in a meaningful, practical way for these people who are marginalized, homeless and faceless. No, they don’t have ready access to care, treatments, support, compassionate care and teaching them the skill sets to be more hopeful, rather than [feeling] helpless … There’s a lot of work to be done,” Abdool said.

Continued education surrounding homelessness and the issues that those who are living and experiencing it is also essential for sustainable progress, especially for first responders.

“A lot more education, a lot more learning opportunities for our first responders, our policemen, our firemen — a lot more in the way of identifying these people, not in a stigmatizing way, but as needing supportive care, rather than to criminalize them and put them in the criminal justice system, where they’re only going to go to prison without treatment, or back on the streets the next day … We ought to take a different approach … we need to do a lot more in the way of meaningful education, in the way of de-stigmatizing, getting rid of some of those myths associated with these people,” Abdool said.

“We’ve come a long way: we’ve included education to police officers and first responders, some of them with mental health training now — it depends on what the call has been about, not unlike with marital discord … but we still see an increase in [for example,] police shooting homeless people carrying a knife … as a matter of fact, those who are chronic victims of mental illness and addictions in our society, they have learned that one effective way to commit suicide is to brandish a knife, and it’s become a common way, now, to be killed … lethal force is lawful.”

Ultimately, having compassion for these people is what needs to be encouraged in order to achieve the goal of ending chronic homelessness in the region. Cheap, short-term fixes won’t result in long-term solutions, and adequate consideration should be implemented beyond finding people beds for one night in shelters that are already overcapacity.

Casting judgement towards others who are suffering from a rising issue that has the potential to affect anyone is what sets us back as a society from productively resolving it.

“Morality and ethics are about values, it’s about [the] choices we make … one of the key messages that we need to [acknowledge] ourselves and share with people we [others] is that we have absolutely no moral authority to judge anyone, be it other family members, in society [etc.] … we cannot stand in judgement of anyone, and we have to start recognizing that at a personal level,” Abdool said.

“The best measure, the best litmus test, for a truly enlightened and civilized society, [the only way] we can make that claim, is how well we protect, serve, and support the most marginalized within that society.”