A walk down Ezra: The history of Laurier’s most resilient party

“There will be no big street party this year, next year, or any other year, because it will be broken up…” Tricia Siemens, Waterloo councillor, in an interview with The Record, April 19, 1995.

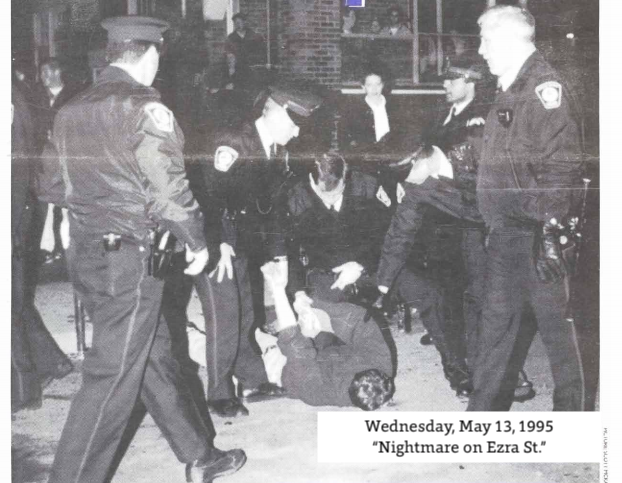

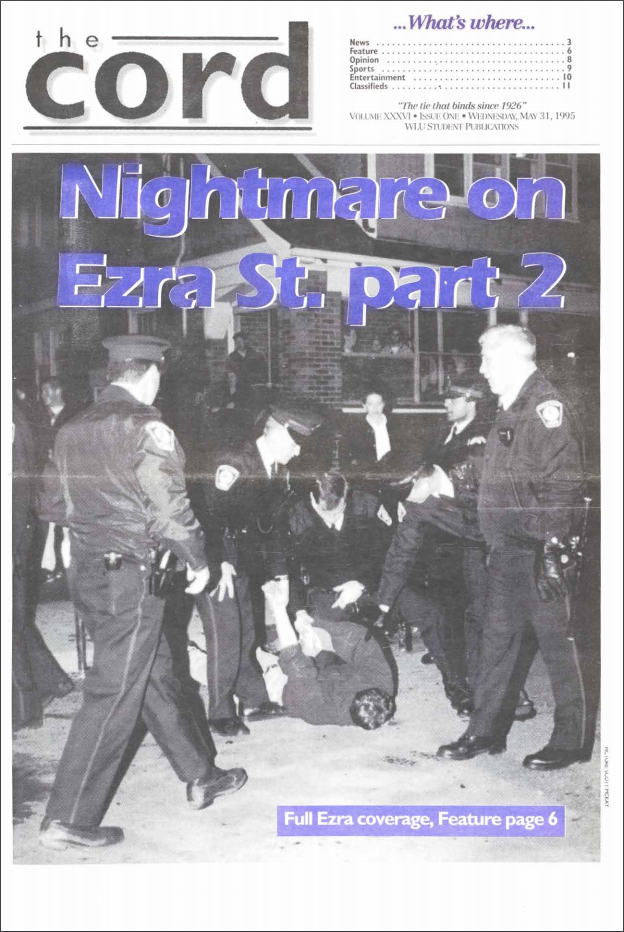

In The Cord’s 1995 coverage of the Ezra Street party, Amanda Dowling wrote about “the largest, wildest version of the annual Ezra Street Party.”

The event hosted 1,500 students and “resulted in 42 arrests, 9 criminal charges and two life-threatening injuries.”

Compared to 2017’s turnout, estimated at between 12,000 to 15,000 attendees, those figures seem like small potatoes.

With the intended undergraduate enrolment at only four years, it seems ingrained in the collective memory of the student body that Ezra has been — and always will be — host to an essential party. But let’s look at how that little circle of debauchery has evolved

Surprisingly, it wasn’t until 2010 that the street hosted its first notable Saint Patrick’s Day celebration. The Cord reported that the police responded to only 25 calls regarding noise and nuisance that day, because the parties along the street were spread out and calm enough to keep it safe, contained and out of the national news.

THE REBIRTH

Following a quieter period of Ezra — a period of around fifteen years — the party as we know it today began with the blossoming of an early spring. “There was this really fabulous Saint Patrick’s Day,” said Phil Champagne, Executive Director and COO of the Students’ Union.

“One of those rare days in the middle of March where it was absolutely gorgeous outside. And people started to hang out.”

“And the next year, much like its cousin 20 years earlier, it started to get a little bit bigger. And then a little bit bigger.”

Since those days, St. Patrick’s Day on Ezra has turned into something else.

High school students show up; other students from across the province come out; buses come in from the US, bringing an international presence to the biggest party of the year, while Laurier’s student population is left with the brunt of the blame for the violence and destruction that comes part and parcel with a party of that magnitude.

But history tends to repeat itself. The Ezra St. party has waxed and waned over the years, and — due to significant efforts by the city and the regional police — it may once again be coming to an end.

THE ORIGINAL PARTY

Nearly 30 years ago, St. Patrick’s Day wasn’t nearly as popular as it is today. But Ezra was still a place where people came together for a big, annual celebration. That party was typically held in the spring, and was typically attended primarily by Laurier students.

“There had been some Ezra Street parties in the early to mid 90s,” Phil Champagne, executive director & COO of the Wilfrid Laurier University Students’ Union. “But those didn’t take place on Saint Patrick’s Day, they usually took place in April.”

“It started small and kind of got bigger with every year… ultimately the city told the university that they had to do something about it and the university came to the Students’ Union and said ‘hey can you help us out with this?’”

That final, infamous party in 1995 — the one that ended it all for fifteen years — gained a mythical status, and is sometimes referred to as the Ezra Street Riot. As the party got out of hand, police gathered up publicly intoxicated students and carted them away. In response, students gathered back on porches and roofs of houses down the street — and began to throw beer bottles at the officers.

Change, it seemed, had to occur. And turning a party of that size — approximately 1,500 students — into something safe and manageable seemed feasible. In order to facilitate for that, the Students’ Union created a giant, year-end bash.

Recognizing the student desire to party and realizing that there was nothing that could really be done to eradicate that entirely, the event aimed to provide a safe, mediated space for students to come out and raucously commemorate the end of exams.

The party was organized in a similar fashion to the O-Week celebration in September and, at its best, hosted up to 3,500 students.

“It was very successful for a long time,” David McMurray, vice-president of student affairs said. “But then the numbers started to dwindle. Students got less interested in that, they wanted to go home. They didn’t want to wait until the 24th of April, the exam schedule didn’t really lend itself to having everyone at one particular time.”

“And then the Ezra Street gathering just organically started to grow.”

THE END?

But that sort of unchecked growth, in perpetuity, is untenable.

The fundamental concern with the Ezra Street party, just like it was back in the 90s, is ensuring that the students and the attendees remain safe — something that is almost impossible with the kind of numbers that attend.

It is important, both to the police and the school, to ensure that property is not damaged or destroyed, and that people aren’t hurt.

Even damage to property is more significant than might be immediately apparent: in previous years groups of intoxicated, thoughtless students have swarmed school buildings just to use the washrooms. Damage to school property has followed as a result of this.

Whether the actions taken to shut down the party this year are effective remains to be seen. The party has been successfully shut down before, but it has reemerged as a different kind of beast — for better or for worse, it is a unique event that attracts attention across the nation.

But the party itself, the event that defines so much of the Laurier experience, will somehow — in one form or another, through adaptation and evolution — find a way to live on.

“I’ve heard the term ‘on the bucket list’, you know?” said David McMurray, “What I’ve seen a lot over the years is the coming and going up and down King and Albert in particular.”

“If you watch the sidewalks you can see people, dressed in green, coming and going, having their own house party and saying, ‘hey, we’ve got to go to Ezra so we can be there.’ And some will stay longer than others. You see a lot of people go in and have a look.”

There are numerous reasons why the celebration has increased so drastically in size, but much of those reasons come down to housing. In around 1993, as the university continued to grow, private citizens began to vacate the area. That left a lot of space to be inevitably filled by university students.

“Waterloo Collegiate High School population, you can tell, started to decline because families were just moving out,” McMurray said. “And students were just kind of taking over the neighbourhood because of the housing piece.”

“Those with means could build a building to hold four or five hundred people … and many did. So the numbers have grown with the enrolment growth of the school.”

As super-structures were put in place to house more and more students, normal sized homes with normal-sized lawns were being torn down. That has left minimal areas for students to hang out.

And fewer lawns and fewer porches have forced the students — along with their open containers — out into the street.

With increased plans for police presence and involvement, this year is a pivotal moment in the history of Laurier’s biggest party. But whether or not this is could be the end of Ezra remains to be seen.

But the party itself, the event that defines so much of the Laurier experience, will somehow — in one form or another, through adaptation and evolution — find a way to live on.