Is scholarly credibility holding us back?

Is the focus on looking back keeping us from moving forward?

Is the focus on looking back keeping us from moving forward? | Graphic by Fani Hsieh

A while back, I was having a standard philosophical conversation with my roommates. No, we weren’t all baked out of our ovens. Most of us were completely sober.

Like many philosophical conversations go, the arguments spiraled from one topic to another in a vortex of linked ideas. One second we were talking about what defines consciousness, the next we were talking about if computer software can have what constitutes as a level of “thinking.” Finally we were off debating the essence of free will. Nothing a bunch of university students haven’t discussed at the end of a Thursday night with a few empty pizza boxes crowded around the couch.

As the clock hit four and the thought of waking up for classes was non-existent, we realized a flaw in the system of academics.

First, the typical question surfaced: “Is humanity innately good?”

Relax — I’m not going to be addressing this widely considered question, and this won’t be turning into some glorified philosophy lecture either.

After registering the question, instead of immediately drawing my own thought, I did what academics have trained students to do whenever asked a provoking question: I delved into the pool of my education.

“Well, it depends on what ‘good’ is,” I said. “You would have to consider what morality falls under. Are we talking Bentham’s theory of utilitarianism? Kant’s theory of deontology? Aristotle’s ideas of responsibility and achieving ultimate happiness, blah blah blah.”

Here’s the problem with my response.

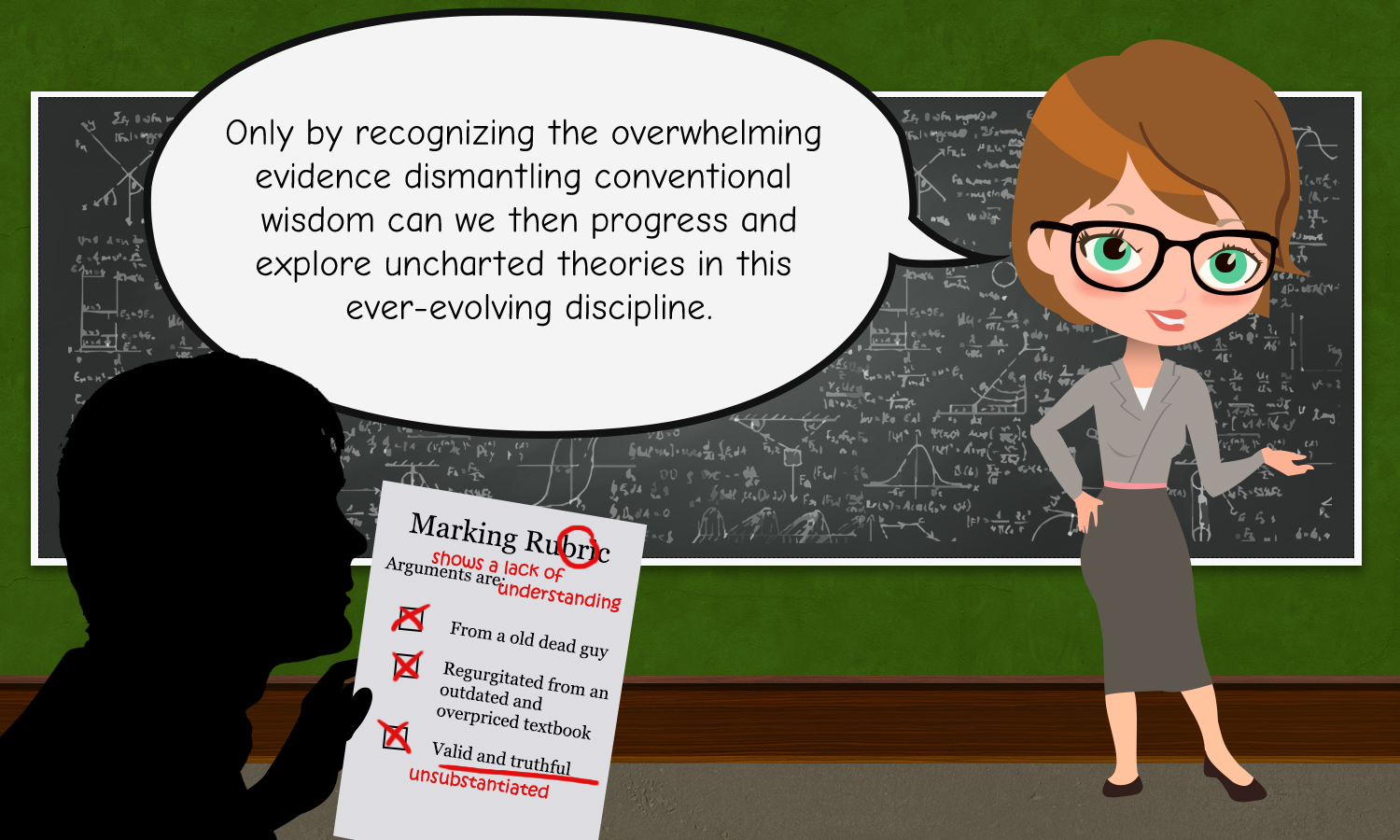

Through the pressures of academics, we have been trained to think through the lenses of other minds. Obviously our thought process is limited to what we are capable of perceiving — in order to develop knowledge, it needs to be acquired through being exposed to current facts. But students are conditioned to articulate theories, internalize what those theories represent and then intuitively jump to conclusions on the trampoline of information available.

Often, it seems we are forced to conform to the system of credibility, where we believe the only way to have trust in our own thinking is to pull out a quote in a textbook that supports the claim. Is this wrong?

I believe the greatest ideas derive from a level of theorist exploration — considering multiple academic arguments and then concluding with your own interpretation, essentially keeping you on track while aboard your train of thought.

Some of the greatest academic ideas are driven forward with the vehicle of academic discussion.

So are we wrong to dismiss thoughts that do not carry some scholarly credibility?

Before getting lost in the search of other philosophers, I inteded to say this: “Out of all the theories, I think I agree with Aristotle and Bentham the most, but I also understand some components of Kant’s deontology in terms of applying consequence to a universal scale.”

But this response continues to feed the problem.

Yes, I am saying what I think and the theories aren’t speaking entirely for me, but I’m not rocketing my thinking without the launching pad of long-gone philosophers who’ve spent their entire drunken lives stressing about the debate I had been having with my roommates over one night.

The structure for an argument, at least according to my philosophy textbook, is as follows: claim, logical premise and conclusion.

Society has a level of expectation when it comes to this form of argumentation. We need sources to back up our claim, we need real life examples to support our logic and we need pre-existing theories to calculate our conclusion.

As the Opinion Editor of The Cord, I am continuously exposed to what makes a piece well-argued and which ones use vague generalizations to support some foggy outlook.

Naturally, as society demands, the best argument comes from personal experience with the interpretation of one or more secondary sources.

However, does the need for credibility in every scholarly essay, exam and project limit our level of thinking to what has already been thought? Is the need to academically source our logic diluting what we are trying to say?

Are our minds constricted to this demand of academic evidence to the point where we are holding ourselves back?

Or is the inclusion of other theories simply cooking our claims into something that can be easier digested by those of the academic community?

Every claim needs some source. That’s just how logic works. Whether the source is scholarly, based on experience or even just some general intuition, you need to have a basis of understanding to link one idea to another.

But the conditioned need for academic credibility should not compromise nor invade the inception of a thought.

Sometimes a realization can break through the realm of what is supported and it should never be shutdown just because there’s no dead guy backing it up in a textbook.

Simply put, while pondering the world’s toughest questions, we shouldn’t only be looking backwards while attempting to accelerate forward.

Assessing the rear-view mirror is important, but we must also remember to keep our eyes on the road ahead.

And for those of you who are still itching for some respected theorist to jump into my claim in order to nod your head with the slightest trace of agreement, I’ll leave you with this.

“The true sign of intelligence is not knowledge, but imagination,” — a quote by Albert Einstein.

According to my sources, that guy’s fairly credible.