Kathryn Bigelow was the wrong choice to direct Detroit

The reception of Kathryn Bigelow’s Detroit, which dramatizes the 1962 Detroit riots, has been thus far split between white and black film critics.

While one side was quick to heap praise onto Bigelow’s latest controversial thriller, a minority of voices in the film criticism community took immediate umbrage with Bigelow’s presumptuousness in tackling such a racially charged story as a white woman.

Angelica Bastien, when writing for RogerEbert.com, called it “directed, written, produced, shot, and edited by white creatives who do not understand the weight of the images they hone in on with an unflinching gaze.”

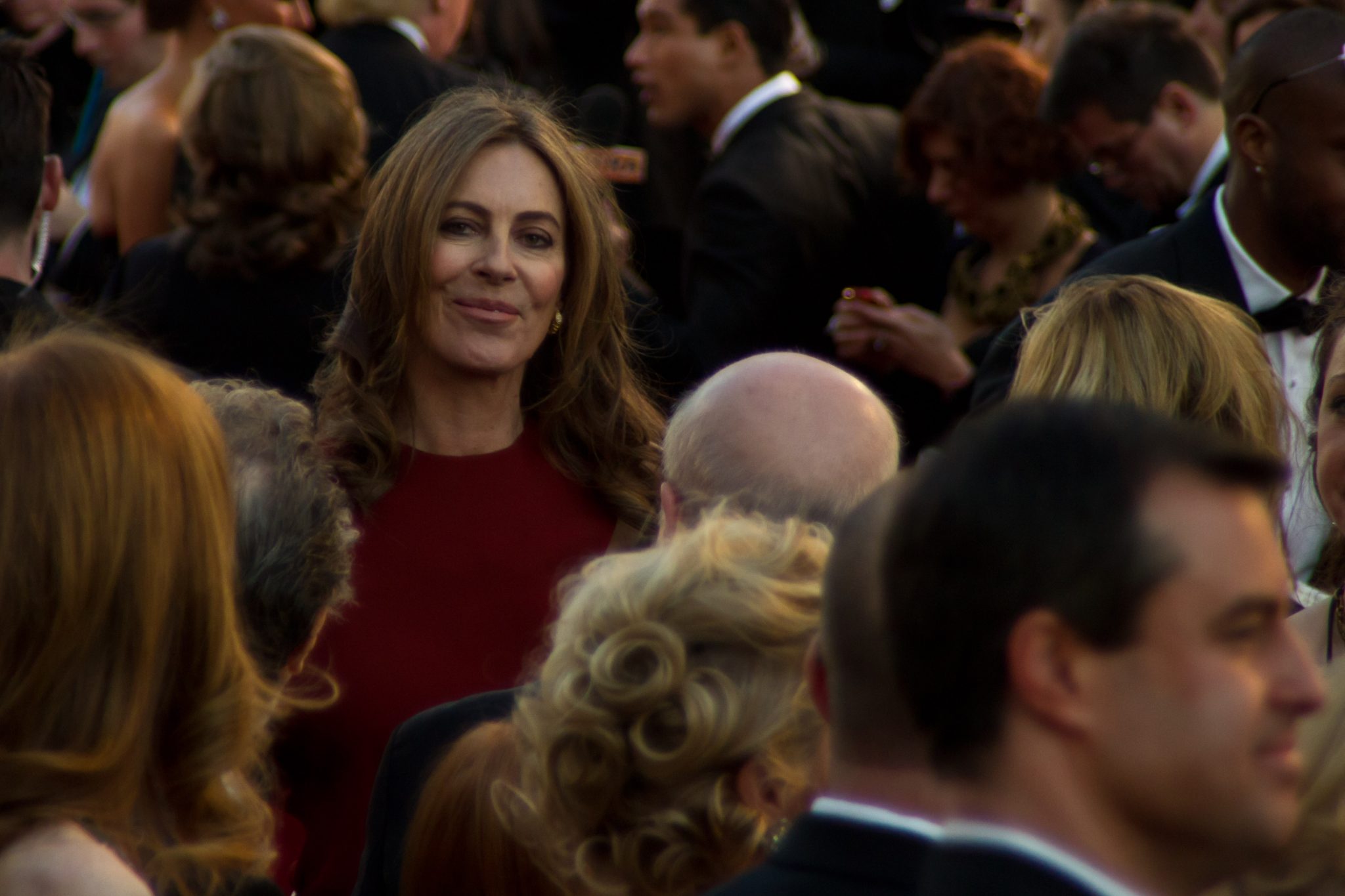

Understandably, Bigelow has proven herself as a director to champion and promote, especially this year, when the absence of female directors in the mainstream has become impossible to ignore. Being the only woman to this date to garner an Oscar for direction, the unanimous support that this production received all through its development doesn’t necessarily shock me, but I am mildly surprised that her involvement didn’t raise eyebrows from the start.

This stark discrepancy in audience reception points to a teachable moment of the 12th Street Riot of Detroit that was adapted to cinema. What exactly in Kathryn Bigelow’s background – as a Californian who would have been only sixteen years in age when this event occurred – would make her qualified to cover such a bleak moment in America’s history of race relations?

Unlike her other projects wherein the anchoring point was reliably a white male or female of middle class origin, Detroit places the focus on black characters, something Bigelow has not dealt with at a starring capacity since Angela Bassett’s leading role in 1995’s Strange Days.

Having now witnessed her attempt, the results were decidedly mixed, but I found myself agreeing with the opposing critics I referenced earlier. Bigelow embodies the event that took place, but it’s undeniable that her understanding is based around shock value and audience manipulation.

Her representation of racial violence was visceral, but ultimately unjustified and deeply problematic in an unshakably tone-deaf way. It was obvious to most in the audience that what we saw was presented by someone who just plain didn’t “get it.”

The failure of Detroit is a reminder that the person telling the story has a huge affect on its reception. Bigelow, even with her attention to accuracy and detail, proved ill-equipped for the greater implications and meanings of the story she shared. What the film needed was someone behind the camera more adept to sensitive portrayals of black characters.

Is it so uncalled for to state that Bigelow was not the right person to tell this story? That a director more savvy – preferably of colour – would have done the event more justice?

From the point of view of an observer – particularly one who has paid attention to Bigelow’s career – nothing immediately points to her capability of handling such a controversial, inflammatory subject. I’m reminded of the fight over Malcolm X, where the initial decision to have Norman Jewison direct – as opposed to Spike Lee, who ended up taking on the project – was met with public outcry.

Despite the strong focus on historical accuracy, Detroit still ended up feeling inauthentic because of the person behind the camera.

Filmmakers need to understand the limits of their own creative potential; whether or not they can tell a story supersedes whether or not they should.